Introduction

Videogame analogies are great. I especially love watching people’s eyes glaze over as I explain social dynamics through the lens of Pokémon type matchups. Good times. I use videogame analogies far too frequently, because apparently a lifetime of playing games has done irreparable damage to my brain and social skills.

I can relate then, to Yakuza: Like a Dragon’s protagonist Ichiban Kasuga, who played Dragon Quest games so obsessively that his imagination begins to overlay RPG elements onto the real world, turning combat encounters into turn-based battles and everyday service and retail jobs into combat classes.

Yakuza: Like a Dragon / Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio

This is, of course, an extremely roundabout way of saying “Let’s look at visual artist job roles as if they were RPG character classes”.

Main Classes

In most RPGs, your first step is picking a main class – a core archetype that defines your playstyle (or in this case, your artistic skillset). Maybe you’ll develop this class further through promotion, like in Fire Emblem, or specialize it in a certain way, like in Baldur’s Gate 3. Or perhaps you’ll mix things up and combine different classes into a hybrid, à la Kingdoms of Amalur. The games industry isn’t much different, though it certainly is a lot harder to figure out if you’ve levelled up or not.

Baldur’s Gate 3 / Larian Studios

Just like with Yakuza: Like a Dragon’s job system, there is absolutely no reason for you to remain forever tied to one class. In fact, depending on the size of your team (or I guess, in this analogy, “party”), you might need to take on more than one role at the same time. In smaller teams, sometimes the Concept Artist and the 3D Artist are one and the same.

Similarly, some more advanced jobs we’ll touch on later require experience in many different areas. So don’t feel “locked in” to one “class” – it’s absolutely worthwhile jumping into other roles every so often and levelling them up a bit.

Like a Dragon is once again a perfect metaphor here. In the game, level up certain Jobs enough, and you unlock permanent skills that you can use across all other classes. The more you learn, the better – and the same applies to the real world. Outside of videogames, we call these “transferable skills”.

Take the increasingly blurry divide between 2D and 3D art – for example, even 2D artists often incorporate 3D into their workflows. Environmental concept artists will often “block out” a scene in 3D to nail the perspective before painting over it. Rogue Legacy 2, despite looking, acting and possibly smelling like a 2D game, is actually made up mostly of 3D models!

Rogue Legacy 2 / Cellar Door Games

When making a game, time is key and deadlines have to be met (insert Majora’s Mask reference here) and so anything that speeds up the workflow is welcomed with open arms.

So let’s take a look at our “core classes”. I’ll let you decide which are the Warrior, Thief and Mage equivalents.

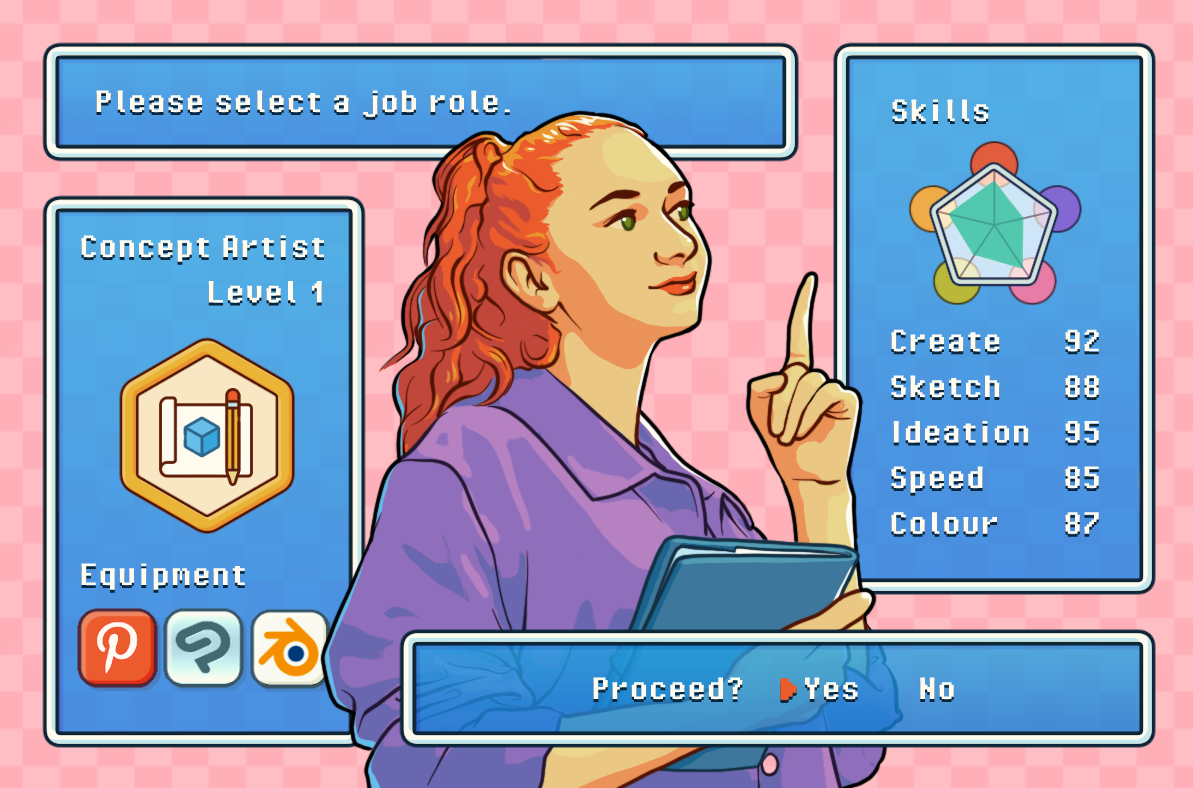

Concept Artist

The Concept Artist is the class that strikes the first blow. They’re the ones handed a vague brief that says, “It’s like Skyrim, but underwater” and tasked with turning it into actual art. If it needs a visual identity (and, spoiler alert, videogames are an almost entirely visual medium), Concept Artists are the ones who sketch it into existence.

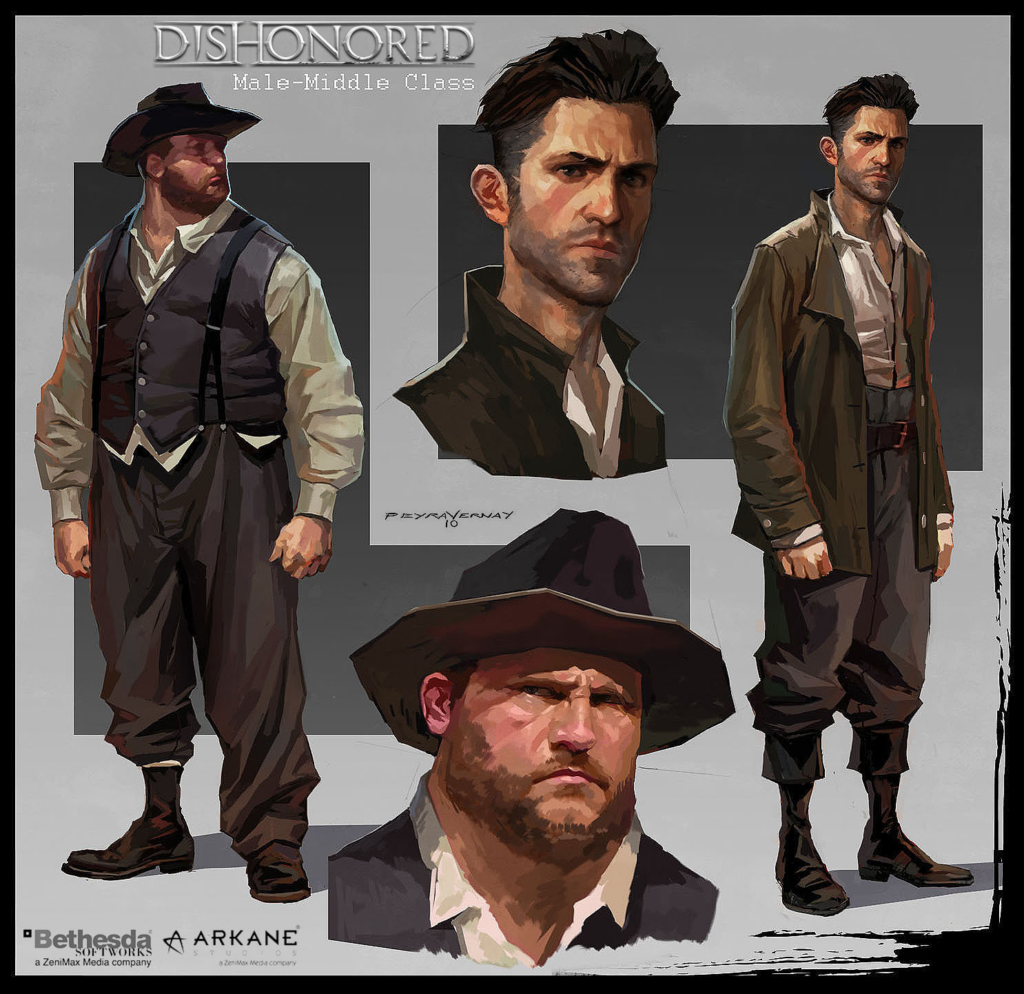

Image credit: Cedric Peyravernay / Arkane Studios

Their work is what sets the tone for everything else. They’re not just designing “cool swords” or “angry dragons” – they’re creating the cool swords and the angry dragons, setting the visual standard for the entire project, sometimes weaving subtle storytelling into the designs as they do so (Elden Ring is a fantastic example of this). Also, the rest of the visual team need them to finish before they can start their own work. No pressure or anything.

Concept Artists usually bat ideas back and forth between themselves and the Art Director, refining it slightly more each time. While we’re prattling out videogame analogies, it’s an awful lot like the “Gannondorf energy ball tennis” that usually pops up at the end of Zelda games. You know the one. Except instead of the final boss taking a chunk of damage at the end, you wind up with a lovely piece of artwork. Which is much nicer, all things considered.

Image credit: Adrien Lucas / Arkane Lyon

Key Skills: Sketching like your life depends on it (which, financially it does, I suppose), composition, abundant creativity, colour theory, and the ability to churn out ten variations of the same monster in a single day.

Starting Equipment: Graphics tablet, digital painting software, a sketchbook, and an ever-growing reference library.

What You’ll Love: Dreaming up wild, fantastical designs before anyone else has a say, and having a huge impact on the overall look of the game.

What You’ll Hate: Offering a selection of concepts to choose from, only for the one you liked least to get chosen. Every. Single. Time.

Legendary Concept Artists: Cedric Peyravernay, Jaime Jones

Further Reading: How Do You Create Concept Art for Video Games?, A Brief Guide to Becoming a Concept Artist

2D Artist

The 2D Artist’s job is to take all the raw assets and give them the love and attention they need to shine. Sprites, textures, menus, backgrounds – if it’s flat and pretty, a 2D Artist probably made it happen. Maybe you’re a pixel artist crafting the minimalism of Minit or conjuring the intricate Gothic horror of Blasphemous. Or perhaps you’re drawing entire assets frame-by-frame for games like Cuphead or Hollow Knight.

Cuphead / Studio MDHR

These days, developers are even making game art out of embroidery, so if it’s flat, it’s fair game. In smaller teams, this role can overlap with a bunch of other responsibilities, like UI design and animation. In bigger studios, it’s a bit more specialized, but the workload still revolves around one core idea: taking what exists and making it look really, really pleasing to human eyeballs.

2D Artists are also often dragged down into the shadowy realm of marketing. Key art, promotional banners, and the game logo all require an artist’s touch. It’s an opportunity to show off the game’s style at a glance and seize the attention of unsuspecting consumers. And also, a chance for marketing to ask for “just a few quick tweaks” two days before launch.

Owlboy / D-Pad Studio

Key Skills: Digital painting, graphic design, colour theory, knowing exactly when to stop fiddling with something before you ruin it.

Starting Equipment: A graphics tablet, digital art software, vector Illustration software. Animation software if that’s also your thing.

What You’ll Love: Seeing your work become the face of the game, from key art to menus, and knowing you’re shaping how players first experience it.

What You’ll Hate: Nudging the same few pixels back and forth for two hours until it “looks right”.

2D Art Legends: Chris Bourassa, Ari Gibson

Further Reading: Working as a 2D Artist at a Game Development Studio, How to Become a Video Game 2D Artist/Animator

3D Artist

The 3D Artist takes the sketches, scribbles, and references from the Concept Artist and transforms them into fully realized 3D models. Characters, props, environments – if it requires three dimensions, it needs a 3D Artist.

Bomb Rush Cyberfunk / Team Reptile

It’s not all glamorous, though. For every main character you get to sculpt, there are a thousand trees, explosive barrels and waist-high crates waiting for their time in the spotlight. Someone has to do it, and unfortunately, that someone is probably you. That doesn’t make it any less important, however!

3D Art is a tricky beast to master, requiring a great many different skillsets (modelling, sculpting, UV unwrapping, texturing, retopology…) but it’s infinitely rewarding when you do, allowing you to create practically anything you can dream of. It’s also increasingly being used quite creatively to make 2D assets, meaning that you can have the best of both worlds.

Maybe you’re more at home sculpting faces or hard-surface modeling a plasma rifle. Either way, you need to keep a close eye on your polygon count and how they impact game performance. That’s a lovely goblin you’ve sculpted, but it’s no good if he drags the framerate to 5fps every time he’s onscreen. Unless that’s an intentional gameplay mechanic, in which case… congratulations?

Final Fantasy VII Remake / Square-Enix

Key Skills: 3D modeling, sculpting, UV mapping, texturing, and knowing how to ‘optimize’ without turning your art into those grapes from Final Fantasy XIV.

Starting Equipment: 3D Modelling software, 3D texturing software, a good PC, infinite patience, a voracious appetite for learning new things.

What You’ll Love: Seeing your work exist in a space players can walk through and explore, and watching as your characters move on their own as if puppeteered by some eldritch magic.

What You’ll Hate: Realizing you can no longer play 3D games without smooshing the camera up against every single 3D object to see if that nook is made of polygons, or just part of the material’s Normal Map.

3D Art Legends: Raf Grassetti, KEOS MASONS

Further Reading: How to be Successful as a Self-Taught 3D Artist, Ultimate Guide to Becoming a Character Artist

Checkpoint

That’s it for now. We’ll almost certainly revisit each of these in the future in more significant detail.

In Part 2, we’ll continue with a look at “Specializations”, because we’re not going to stop until this analogy has been firmly driven into the ground. See you then!